Chapter 9: Charlton - more adventures

An annual event in Charlton was the Agricultural Show. This was a mix of competitive events and fairground entertainments. On the competitive side, there was the log-chopping competition that sometimes left me wondering how the axemen came away with both feet. On the safer side, there were art and photographic competitions, and ones for the fastest sprinter, best scones, best cream cakes and biggest vegetables, etc etc.

On the entertainment side, there were fairground attractions such as a merry-go-round and stalls that required a variety of skills to win rather useless prizes.

Most of all I enjoyed the machines that made fairy floss and ring donuts.

There was sometimes a boxing tent in which a fairground boxer — usually an Aborigine — would invite locals to try their luck in the ring. The contests were never to be taken seriously as there was a strong element of fakery in the results. For several reasons I never cared for these events. I had done a bit of harmless boxing in scouts, but it never seemed sensible for two grown men to be bashing the daylights out of each other, particularly hitting each other on the head and perhaps causing long-term brain damage.

One year I was chosen to be judge of the agricultural show’s art competition. I was still in my late teens or early twenties. There was fury from the wife of one of the town dignitaries when I didn’t give her painting of a single rose a prize. I told her that it was poorly composed, but she said the placing of the rose to one side of the frame was the modern thing to do. No surprise that I was never asked to be a judge again.

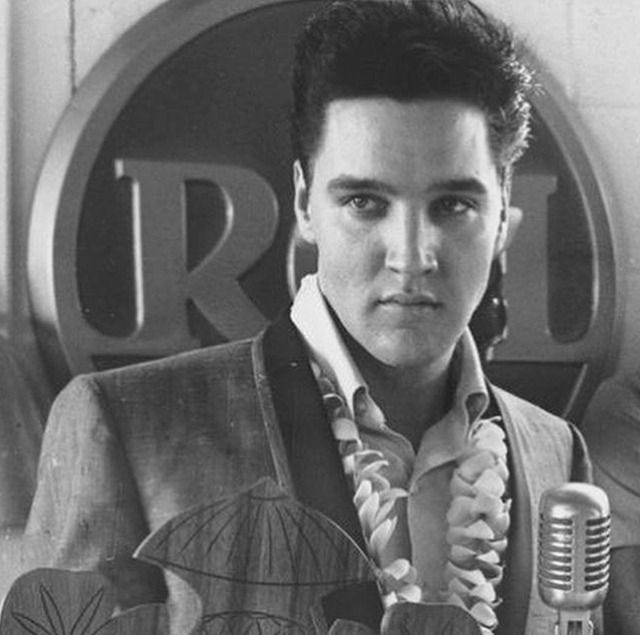

It was a tradition in my family to listen to the breakfast news and Russ Tyson’s Breakfast Half Hour on ABC radio. I had a moderate interest in both. Then one morning Russ thought we might be amused by a song by an American singer called Elvis Presley. It was Heartbreak Hotel. Wow! Russ might have played it as a joke, but it opened a whole new musical world to me. Elvis was even better than Bill Haley and his Comets with Rock Around The Clock. I still love all the songs from that period.

Still on the subject of music. My mother thought it would be a good idea if I learned to play the piano. I agreed, but it didn’t turn out as we expected. I wanted to play pop music, but the piano teacher, Elsa Paterson, had other ideas. We rubbed along for a while and I did okay in my first exam. But I got fed up with her striking me across the knuckles with a ruler whenever I made a mistake, which was quite often. Eventually, I told her that if she did it one more time, I would walk out. She did and I did. Not since that day have I touched a piano keyboard. That might say more about me than it does of Elsa Paterson. I have since learned that I wasn’t the only who strongly objected to her teaching method, but I don’t know if any others walked out on her.

Does anyone still play marbles? It was the only “sport” in which I was passably good. As already explained, cricket, football and tennis were disaster areas for me. The hearts of team captains must have sunk if they were lumbered with me. But marbles were okay and they were attractive to collect.

The Data Protection Act didn’t apply when I worked for the Tribune, Wycheproof News and Quambatook Times. Arguably the most popular column in all three papers was headed Personal Pars. This recorded everyone who was on holiday and where. Visitors to the town also got a mention. More importantly it listed all those in hospital, often specifying their medical complaint. It was our practice to phone the hospital on the eve of the publication date and speak to the matron who would give us a run down on all her patients. If the ailment was a bit on the embarrassing side, it wasn’t mentioned, but broken limbs and how they came to be broken would get a mention. Ditto non-embarrassing hernia, tonsils, heart and appendix operations were often specified. As far as I know, none of the patients was asked if they minded being mentioned in the newspaper.

I reported cases that came up in the Charlton Magistrates Court and it was there that I came across Eric Shackleton Bailey, a barrister and solicitor who lived in the neighbouring town of Wedderburn and who also had an office in Charlton. “Shack” as he was widely known — full name Eric Alfred George Shackleton Bailey — was a very scruffy Englishman who rarely managed to shave all of his face at the one time. We would come across each other when I was reporting a court case and he was the barrister for the defence. He had a habit of strutting around the court in the theatrical manner of Rumpole of the Bailey, all the while chewing on a straw from a straw broom.

Whenever there was a break in the court proceedings he would approach me for my thoughts on how he was doing. I can’t say that my thoughts were of much use to him.

Over a period of time “Shack” and I got to know each other reasonably well, although I would never claim we were friends. At one point, he admitted to me that he was a “remittance man” from a very posh English family who found him an embarrassment. A “remittance man” was someone who was paid to move abroad and stay there in return for regular payments from his family. His father, the Revd John Shackleton Bailey, was headmaster at a private school and earned notoriety for the savage beating of a pupil caught smoking. “Shack’s” brother, David, was an eccentric but highly regarded academic who married Hilary Amis, the divorced wife of Kingsley Amis, the noted novelist and poet.

My family history detective wife, Rosemary, was intrigued by “Shack” and discovered that he was once a British Conservative Party politician. He was elected, aged 26, as Member of Parliament for Manchester Gorton in the Conservative landslide victory at the 1931 general election, the only time that Labour had lost that seat since 1906. Bailey held Gorton until 1935, when it was regained by Joseph Compton, the Labour MP who he had ousted in 1931. During World War Two he joined the King’s Own Regiment (Lancaster) then sailed to Australia from London in 1950. Rosemary also discovered that a reason for his being sent to Australia was because of accusations that he had been involved in the black market. (More on “Shack” in a later chapter.)

I haven’t been able to find a photograph of “Shack”, but this is one of David who looked very much like him:

Having disposed of my motorbike as a danger to my life, I bought my first car, a Vauxhall, from my Uncle John Ross who had cared for it lovingly. I don’t think he would have been pleased to learn that I drove it in at least one Charlton Rotary Club car rally. I never won anything:

The Vauxhall developed very expensive engine faults, and after being repaired, I sold it and, going up to my neck in debt, bought a lovely VW Beetle, one of the first cars to be heated inside.

I loved the thought of flying and was quick to join the relatively short-lived Charlton Aero Club when it started up.

My brother, Jeffrey, was a natural pilot and was allowed to fly solo hours before it was legal for him to do so. He never completed his flying training because of a nasty head injury received in a road accident. Not pictured is my friend Dan O’Connor who was the only member of the club to become a commercial pilot. I never got around to getting a full pilot’s licence because I spent far too much time doing aerobatics with the instructor, Bill Parow, who was a former fighter pilot. We even tried flying the open-top plane upside down after making absolutely sure the seat belts were firmly done up.

Next chapter: my final years as a resident of Charlton

Fascinating to see this. Eric Shackleton Bailey was my great great uncle. My mother remembers him and Dora coming over to Cambridge, England for a reunion with his brothers and sister. They all had a difficult childhood which made them quite eccentric people (Eric was by far the most normal). The family story was that Eric was involved in the black market whilst serving in wartime Italy.