Chapter 3: Charlton - my very early years

I have done my best to accurately and honestly report the events I am recounting, but some of the dates and sequences may be inaccurate. Readers who spot errors can feel free to inform me of these. I will not be offended.

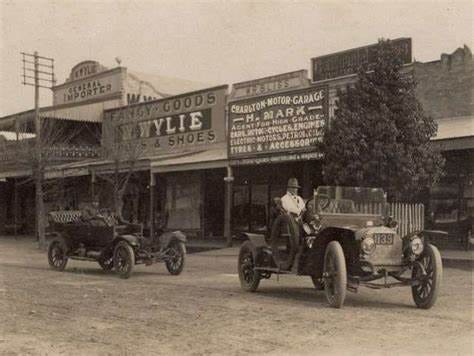

As far as I can establish, we moved to Charlton from St Arnaud in May 1943 when my father, John S Richardson, re-opened the Tribune premises in the two-storey Wylie Building at 26 High Street.

Charlton is a very pleasant town astride the Avoca River, with the northern hill side in the Mallee region and the lower side with its shopping parade in the Wimmera region.

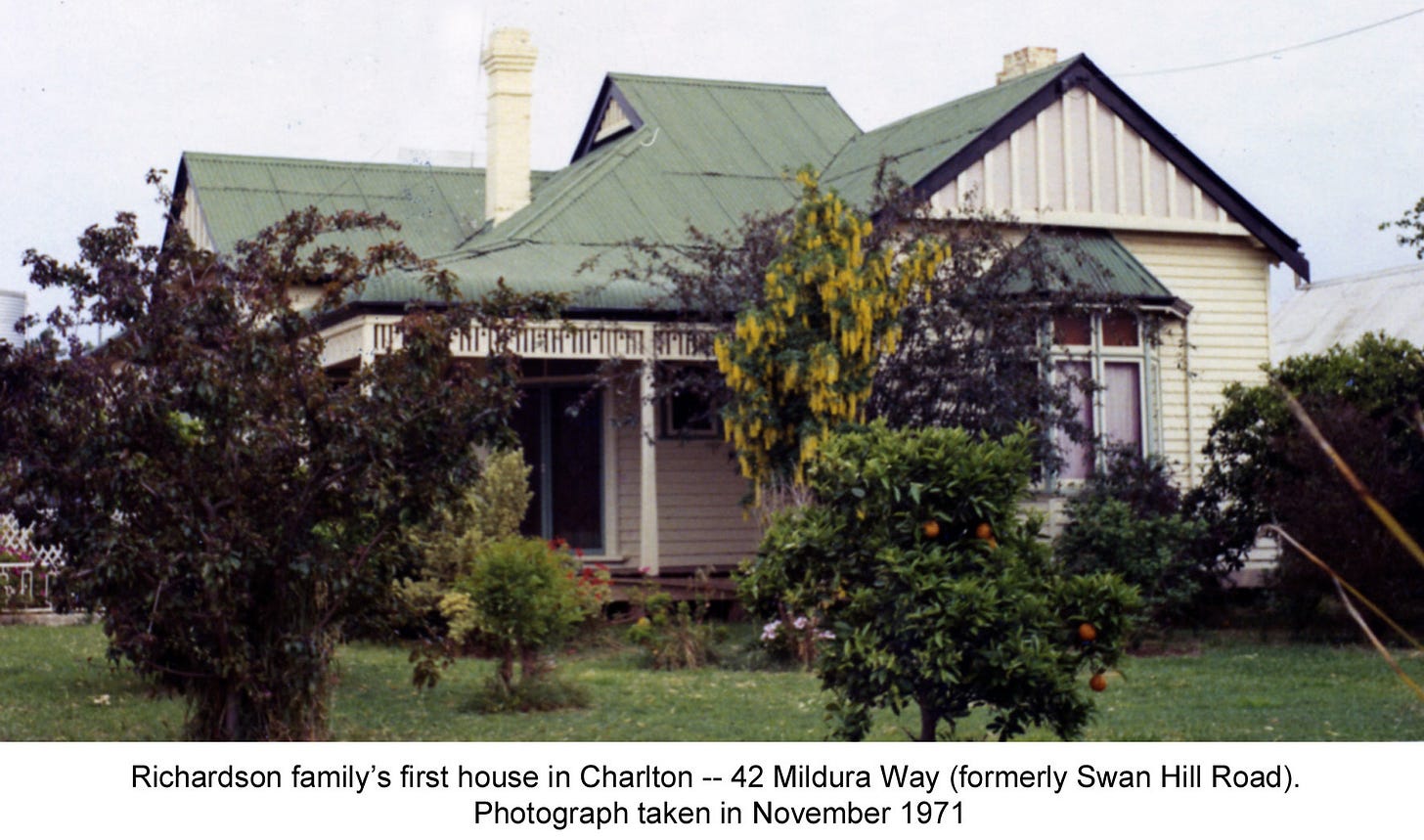

Our first home was 42 Mildura Way (previously known as Swan Hill Road). It was rented, not purchased.

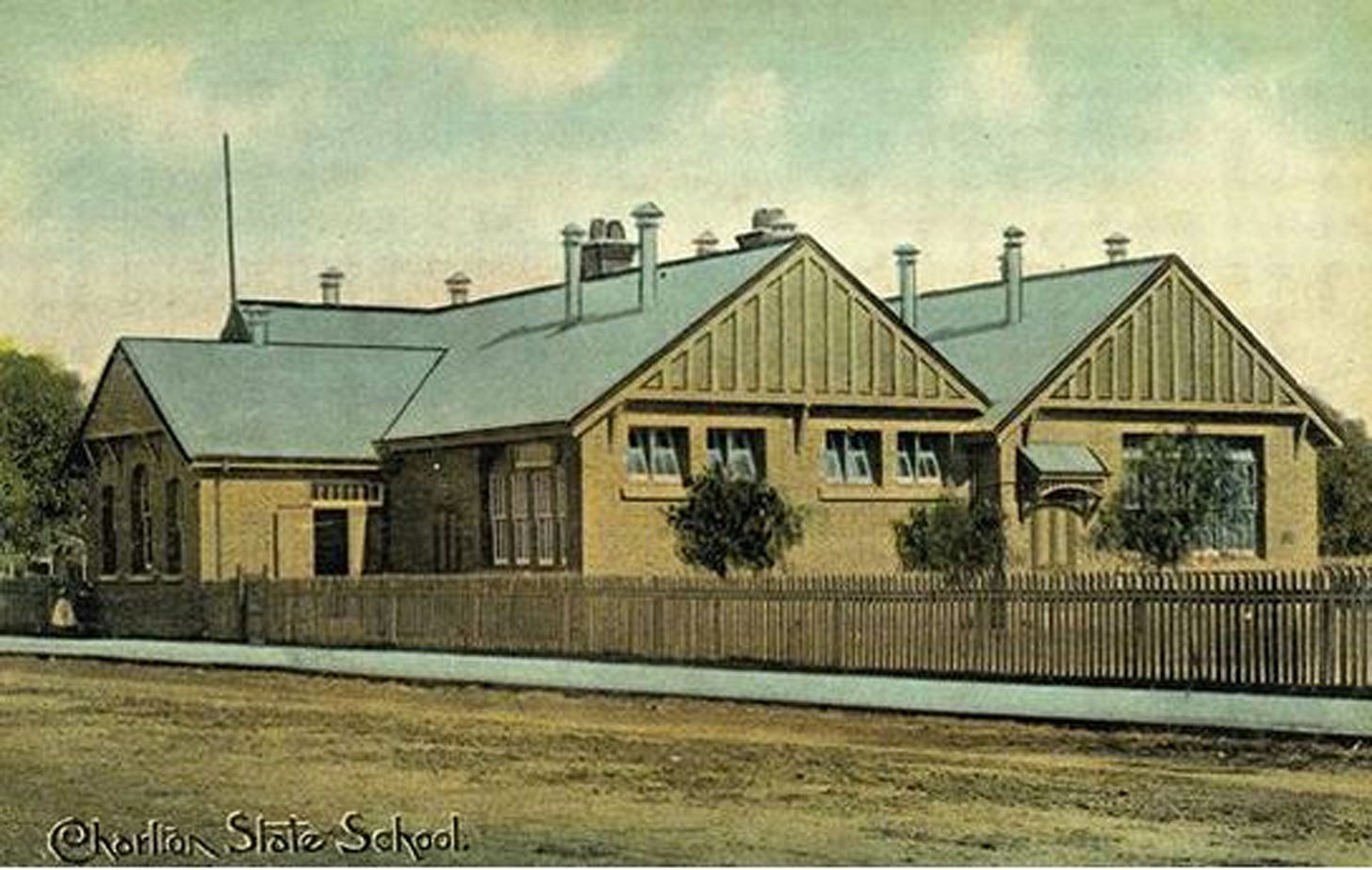

The Wright family were neighbours, and their daughter Averil was assigned to take me to the State Primary School in Learmonth Street on my first few days there.

It was a humiliating experience for a lad of my tenders years, being taken to school by a girl. Worse, I was told that I should hold her hand.

I was thrilled to meet Averil in the Back-to-Charlton celebrations in 2013. She remembered me but hadn’t recalled my embarrassment so many decades before. I assured her that I had grown up since then and quite liked holding a female hand. We had a good laugh.

I guess Averil and I travelled to school along what I remember as the “back way” over the low bridge crossing the Avoca River. In later years I preferred going over the shorter railway bridge, which was great fun if it coincided with a train travelling over that bridge just feet away.

My thoughts about the primary school were mixed. I remember just two of the teachers: Sylvia Tinetti and Betty Trask.

Let’s not beat about the bush. Miss Tinetti should never have been allowed anywhere near the teaching profession. When she was in Charlton she rented a room in the Cricket Club Hotel and her pupils were encouraged to gather outside it each morning to wait for her to emerge and hand her books to her chosen one. The pupils then escorted her along Learmonth Street to the school. Once inside the classroom we were given our tasks and she opened a huge dictionary on a stand to help her with her daily crosswords. Total silence was the order of the day. It is possible that I learned something while in her class, but I can’t remember what it was.

Miss Tinetti was a frustrated theatre producer and the highlight for her each year was to take total charge of the school concerts to the exclusion of almost everything else. On one occasion I was sent home with request that my mother make a number of American Indian outfits for a concert. My mother refused, quite possibly because she was pregnant with her fourth child, my younger sister Alison, born in the Bush Nursing Hospital, Charlton, in November 1945. Miss Tinetti did not take this refusal well, and as was her wont, set about humiliating me before the rest of the class.

To put it bluntly, she was out of control. The headmaster couldn’t control her and parents were mostly too frightened to complain. She was considered untouchable. She died in Daylesford and had never married. No surprise there.

Elizabeth “Betty” Trask was altogether different. I liked her, but she did find her unruly class rather difficult to handle. Her preferred form of punishment was “lines”. “I will not talk in class”, that sort of thing, over and over. The number was increased for those who kept misbehaving. In winter, the classrooms were heated by kerosene fuelled heater like this one:

The heaters got fiercely hot and if we pushed a plastic pen against them — which we did — they gave off a terrible smell. My friend and classmate, John O’Brien, was a repeated offender. At one point I think he was given 5,000 lines, which was ridiculous. Anyway, John and I tied a number of pens to a stick so that he could write multiple lines at the same time. It didn’t quite work, and I think there came a point when Betty Trask gave up on disciplining him.

I started out writing with my left hand, which was not approved back then. Towards the end of my time in the Primary School I was forced to write with my right hand. This was not easy, particularly so when I moved to the adjacent Higher Elementary School and was expected to take lots of notes. I think I was in the last year when it was Education Department policy to have everyone writing with their right hand. Some deeply religious bigots regarded being left handed as “a mark of the Devil”. My wife, who’s several years younger than me, is left handed and wasn’t made to switch. Later, when I joined the BBC World Service, my colleagues got used to me working with pens in both hands as I edited news stories.

We weren’t in the house in Mildura Way/Swan Hill Road for very long. Just months, I think, before moving south of the river to the Wylies Building, 26 High Street, which contained the Tribune and accommodation above and behind it. The bedrooms were upstairs and at the back were the kitchen, dining area and a bathroom with a kindling heater for the bath water.

The back yard was large with a sizeable ramshackle shed. My brother Jeffrey and I (and possibly sister Ruth) decided that it would be a great idea to sleep in makeshift beds in the shed one night. It wasn’t. There were all sorts of sounds, not least made by possums and whoever knows what else, real and imagined. After an hour or two we crept back to the security of the house and our more comfortable beds.

More successful was the underground bunker Jeff and I dug in the back yard. It was a fair size, big enough for us kids to sit comfortably inside. Somehow, we also fitted it out with a barbecue fire, complete with chimney. The roof was not great. If we hit our heads against it, earth would come in between the gaps. I remember that one time when we inexpertly cooked sausages in the fire, my mother looked in and observed: “If I fed those to you in the house you would refuse to eat them!” She wasn’t wrong. On reflection, Jeff and I were surprised that we not just ate the badly cooked sausages with the roof dirt rubbed off, but that we didn’t suffer from carbon dioxide poisoning due to poor ventilation.

There was a deep covered well beside the house in the back yard, but as far as I remember it wasn’t used for anything, certainly not for drinking,

I mustn’t forget the dunny (toilet) with its foul-smelling, disease-spreading pans, collected once a week by the “night soil” man who emptied the contents into a pit outside the town. As the dunny was outside the house, everyone needed a pot under the bed to pee in during the night. This was particularly so during the cold winter nights.

Possums were a problem downstairs at the back of the Wylie Building. They got into the roof and caused lots of noise and quite a bit of stink. They were eventually dealt with, but I don’t know how. Poisoned, maybe?

On a more pleasant note, there was a rabbit hutch built for us by local handyman, Jimmy “The Dog” Rankin, who lived in a hut in Halliday Street. Jimmy got his name because he took a small white dog with him wherever he went around the town. The rabbits were either white or orange, not the usual grey, and were given to us by a neighbour, Percy Jane, who made a living selling rabbits for their meat and skins. The rabbits had a home within the hutch. My sister Ruth was frustrated if they retreated out of sight. Jimmy advised her that rabbits loved milk thistles and they would come out if she could “make the sound of milk thistles growing”.

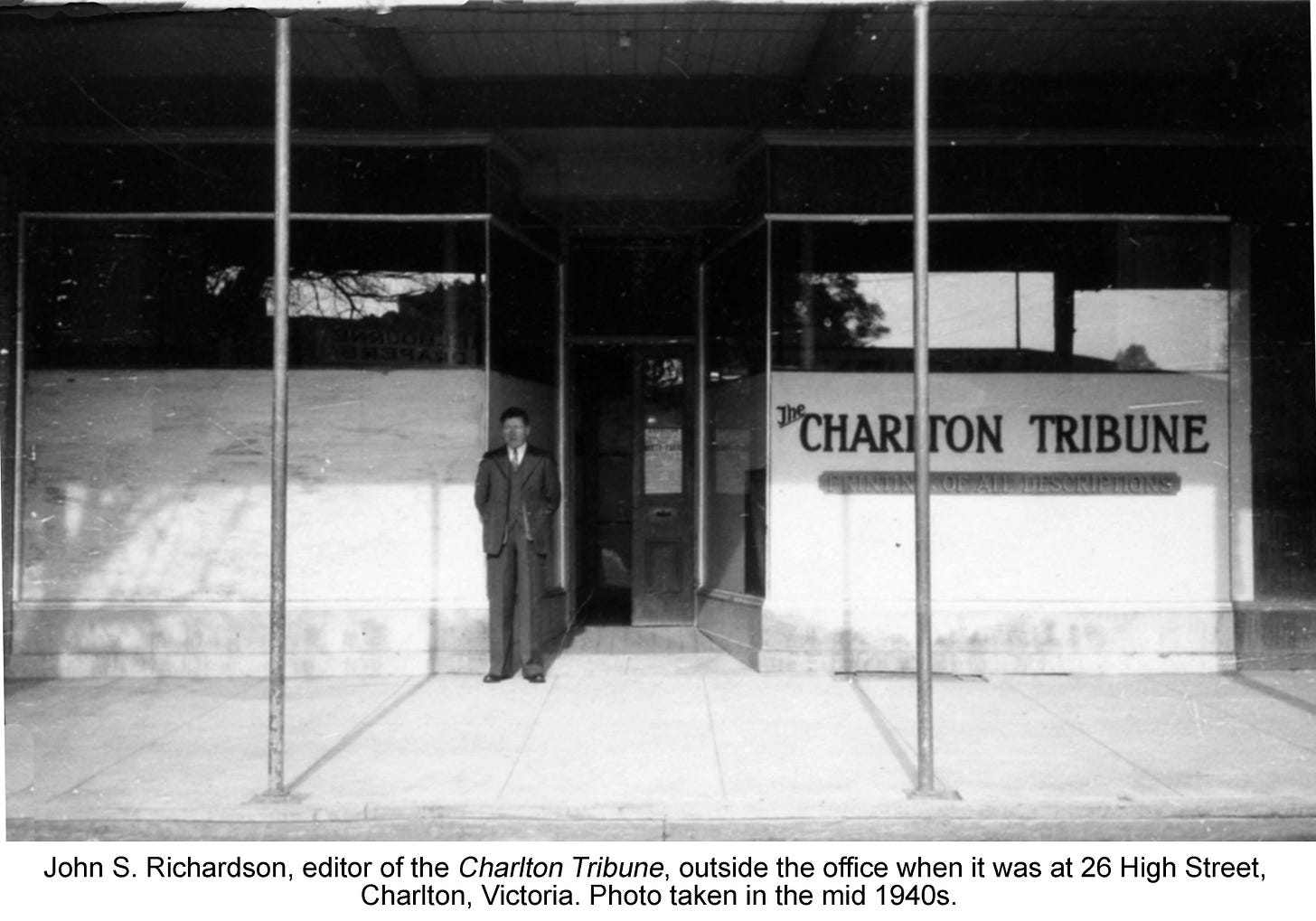

Dad’s progressive involvement with the Charlton Tribune was interesting. The first step was to be appointed by the Melbourne-based owner Mr H A Davies as Managing Editor for £8 a week plus 20% of the profits. His first issue in that role was May 28, 1943. Later, he was described as “Editor and Lessee”. The first issue with him listed as “proprietor” was not until March 1, 1946. Here he is outside the Tribune office in the Wylie Building.

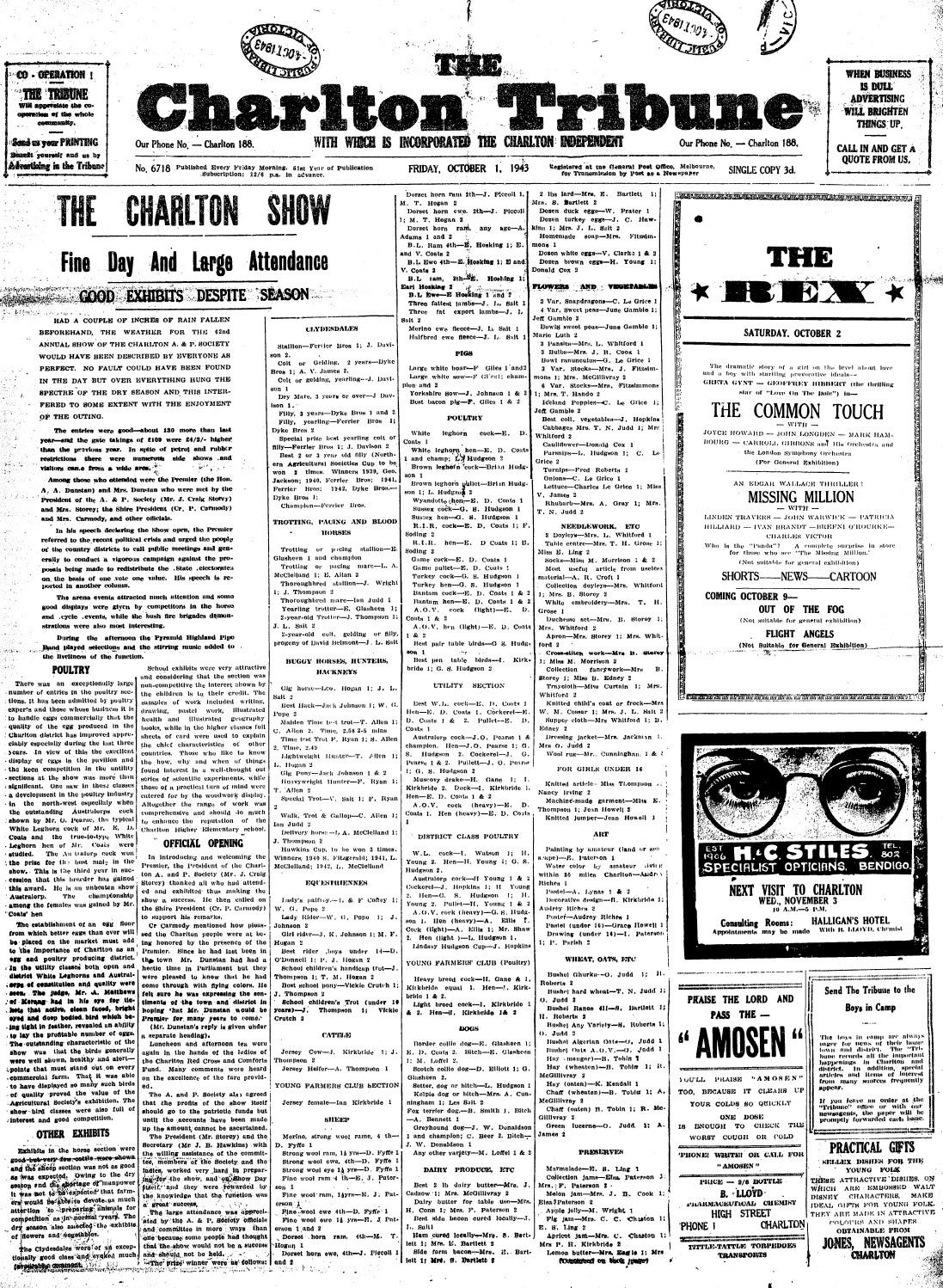

Here’s a copy of the front page of an early edition of the Tribune produced by my father. Because of paper rationing, it ran to just four pages, costing three pence. It had a saturation circulation of about 1000, many copies being posted to people living outside the town.

When my father re-opened the Tribune premises and got all the printing equipment working again, he opened a front office that took job printing (wedding invitations, leaflets and letterheads and the like) and carried a stock of stationary. As my mother was very busy being a wife and mother, Dad needed someone to run the front office. He recruited Edna Ronald, later to become the wife of Edward Parish. An important part of her responsibilities was to proof read Tribune stories and check printing jobs for their accuracy. (Edna and I remained good friends for the rest of her long life.)

Apart from running the Tribune business, Dad did lay preaching in various Charlton and district churches, and during the war years he spent half a day each week sitting in a shelter in the Charlton Park as a member of the Volunteer Air Observers Corps. He was equipped with binoculars to watch for any Japanese warplanes. As far as I know, he never spotted any planes, Japanese or from anywhere else.

We were very poor in those days. Having sold his T Model Ford in Wonthaggi so that he could afford to get married, Dad never again owned a motor vehicle. He either got lifts from people with cars or rode his bicycle to meetings and other engagements.

That said, we never starved. We had access to lots of fruit trees and had chooks (domestic fowl) to provide bountiful supplies of eggs and occasionally meat when the more elderly ones had their heads chopped off and their souls were sent to see their chook-maker. There were also plentiful rabbits. From time to time, we had cream as a treat, given to Dad as a reward for taking a service in one of the churches in the Charlton Shire’s farming districts.

For a while we couldn’t afford a radio. We were sometimes loaned one by Barney Allen, a friend and a town bread baker. Eventually, Barney either sold or gave it to us. It was a strange device, run partly from the local DC electricity and a two-volt wet battery that had to be re-charged from time to time for a shilling at a local garage. Dad became a devoted radio listener and would give me a clip around the ears if ever I made a noise during a news bulletin, or worse during Blue Hills, the drama series introduced by the ABC in 1948. My father’s full obituary can be found HERE.

There was a tragedy in the family during a visit from Melbourne by my maternal grandmother, Ethel C Cox (née Sutton). She had a massive stroke from which she never recovered. She was just 63. Sadly, I didn’t know her well. She was adored by my mother and her siblings, but I remember her as rather unsmiling on the few occasions I saw her. Not that she had a lot to smile about, stuck with my deeply unpleasant grandfather and having lost a son, Alex, whose RAAF Wellington Bomber went down in the North Sea returning from a bombing raid on a German U Boat base in 1941.

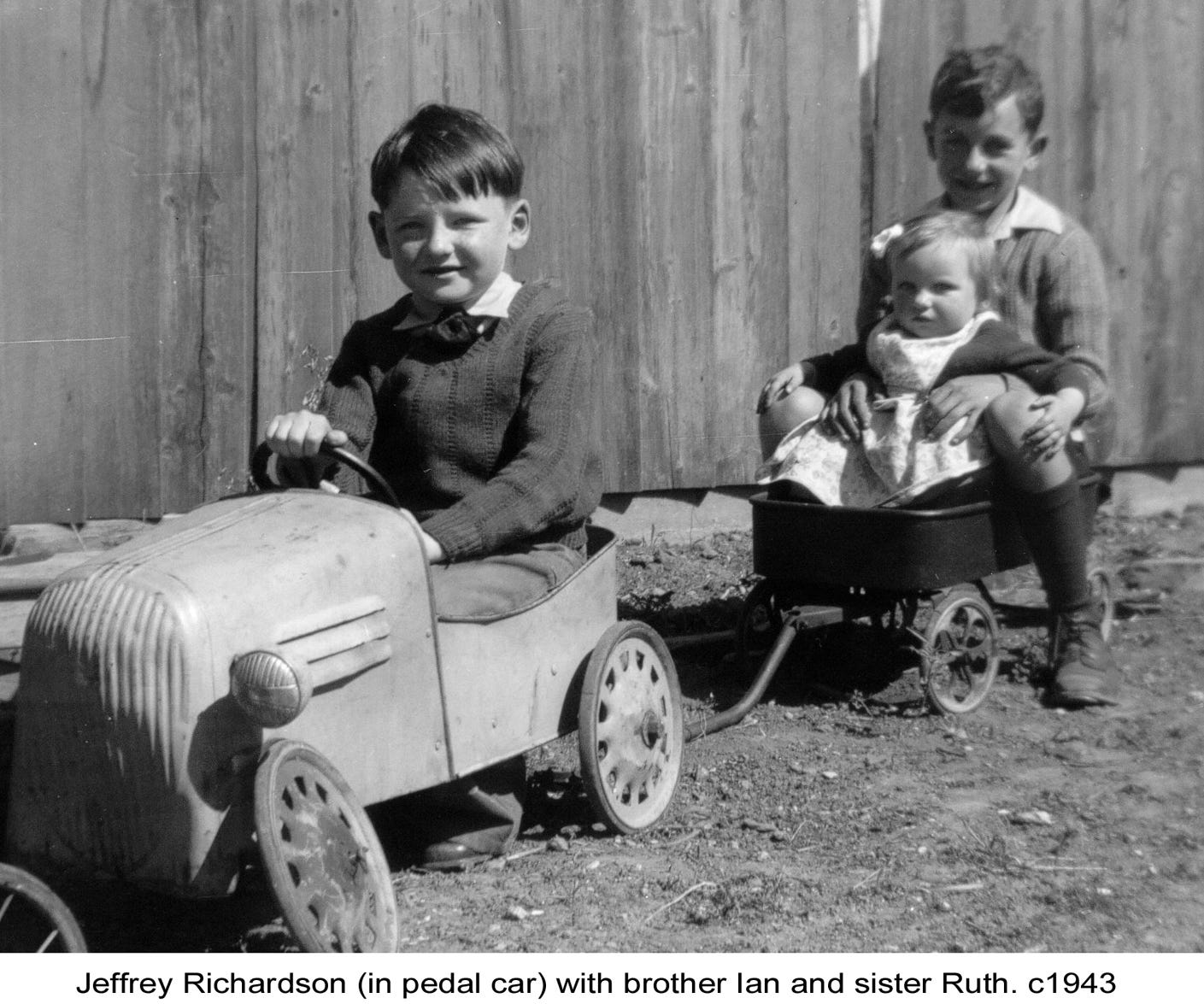

I loved living in the Wylie’s Building. One of the peculiar pleasures was climbing up the poles holding up the veranda at the front. I also had a tricycle which I enjoyed riding, not to mention a very old second hand pedal car and trailer which we kids acquired from somewhere:

I was riding my tricycle on the footpath outside the Tribune office one summer’s day when my father emerged and hurried me inside. I could see why. A dust storm was heading our way from the Mallee. It was a huge black cloud, like this one, that turned day into night. It was not even possible to see across the High Street except for the pinpricks that were the street lights that had been turned on:

I can’t remember how long the storm lasted, but it was an extraordinary sight (or rather experience) and was followed by heavy rain. The house inside and the Tribune shop were a mess. Black dust was everywhere and into everything. Back then we had a Coolgardie Safe, rather than a refrigerator, and I remember the butter and everything inside it was covered in black dust. It took ages to clean everything.

Finally, in this chapter, another memorable occasion: all the pupils at the Charlton Higher Elementary and primary schools were ushered into a room with a large console radio to hear Winston Churchill’s address to the Commonwealth on VE (Victory in Europe) day, in May 1945.

You can watch a film of it HERE.

Next in Chapter 4: Our move to Peel Street and my adventures there and in the Higher Elementary School