Chapter 27: Discovering English ancestors

Revelations about who went before us in London...

As always, this chapter draws heavily on letters that my wife Rosemary and I wrote to our families in Australia and which were returned to us decades later…

Although growing up in Australia for more than 30 years, I had always known that I was half Scottish. That was chiefly because my father, John S Richardson III, retained his soft Glaswegian accent throughout his life. But what about the other half? Was it English? Yes it was, but we had no details.

Soon after my wife Rosemary and I arrived in London in 1968 we set about exploring the English connection and what we found was fascinating. We discovered that my maternal Cox ancestors had lived in Southwark (pronounced suth-ark) one of the oldest parts of London, for more than a century, and we traced Rosemary’s paternal family, Batson, to a lovely village in Northamptonshire. (More on the Batson discoveries in later chapters.)

My Cox ancestors were in the hat trade in several addresses, most within sight of the old London Bridge and the new one that was built alongside it. This new one was constructed between 1825 and 1831 and the old one was then demolished after being in place for 600 years. (For more on London Bridge go to the London Bridge Museum.)

Borough High Street, Southwark, the southern approach to London Bridge, is one of the oldest streets in the London area. The northern part was re-aligned when the bridge was rebuilt. The Penny Magazine of October 14, 1837 gives this description: "We are in High Street with its town hall, and church, and shop-like post office; and here we might imagine we were in the main street of a bustling country town. Upwards of one half of the hop dealers of the metropolis have their shops or establishments in the High Street; and of the remainder the greater portion are in the immediate neighbourhood. The other occupants of the High Street are dealers of every description, woollen and linen drapers, butchers, cheesemongers, hardware merchants, surgeons, chemists, tobacconists, tea dealers, etc, with sundry waggon-inns and public houses."

The neighbourhood immediately south of the bridge, traditionally known as The Borough, had the longest known history of any part of the London area apart from the City. Everywhere below the surface are remains of the Roman settlements on the south bank of the Thames, opposite what was known by the Romans as Londinium.

Southwark in much of the 1800s was not a nice or healthy place to live. The streets were dirty and the River Thames was a sewer. The worst period was known as The Great Stink during July and August 1858 when the hot weather exacerbated the smell of untreated human waste and industrial effluent on the river banks. The problem had been mounting for some years, with an ageing and inadequate sewer system that emptied directly into the river.

The smell, and fears of its possible effects, prompted action from the national and local administrators who had been considering possible solutions for the problem. The authorities accepted a proposal from the civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette to move the effluent eastwards along a series of interconnecting sewers that sloped towards outfalls beyond the metropolitan area. Work on new Northern and Southern Outfall Sewers started at the beginning of 1859 and lasted until 1875.

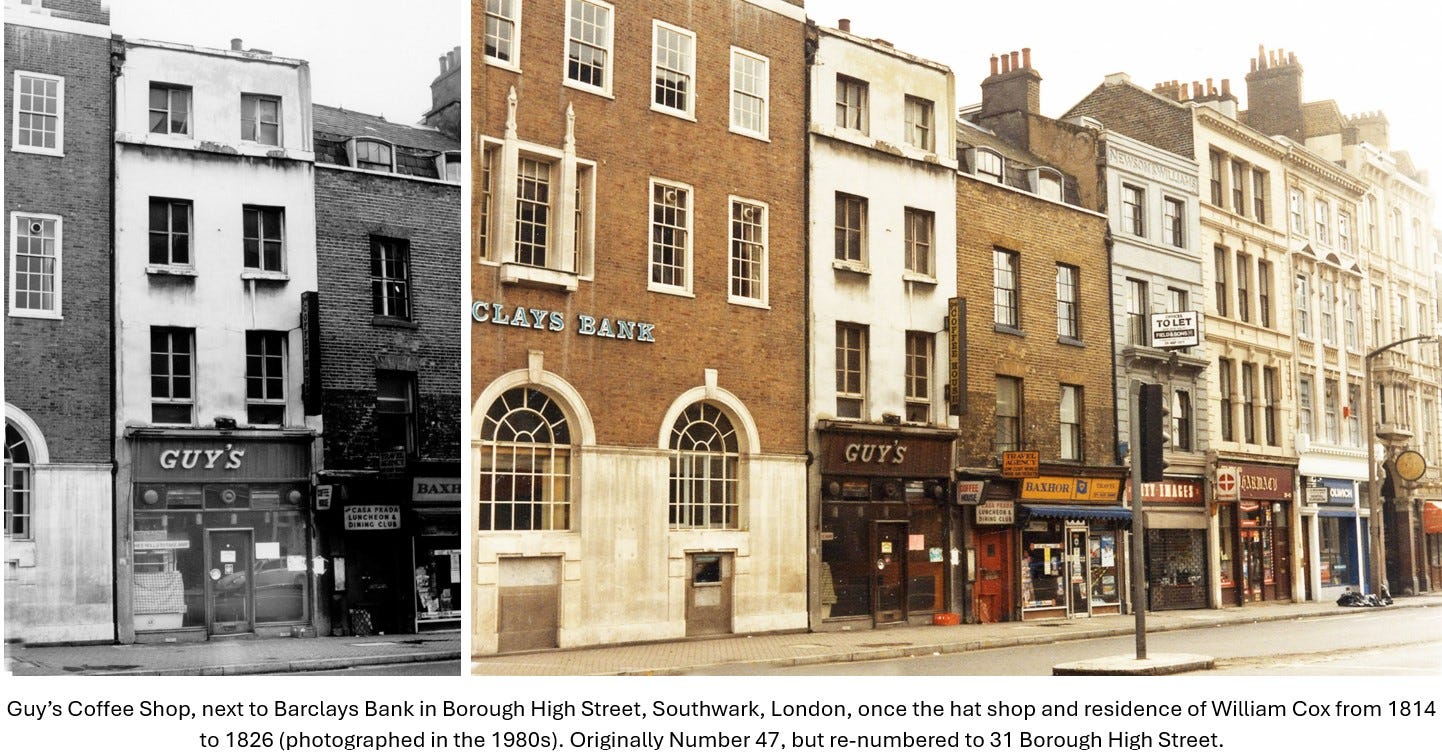

We found one of the Cox addresses in Borough High Street that had escaped the attentions of Hitler and property developers. It was a listed (i.e. preserved) building where William Cox and family lived and where he had his hat shop between 1814 and 1826. William was my great, great, great grandfather.

Around 1994 Transport for London got the preservation listing lifted so it could demolish it and the two adjacent buildings for a new entrance to London Bridge underground and overground station.

As far as I can tell, my maternal Cox ancestors arrived in Southwark about 1771 when Thomas and Mary Cox moved there from Frome (pronounced froom) in Somerset via a period in Scale Lane, Hull, in northern England. Thomas was my four times great grandfather.

One of their children was William who was obviously very active in the bedroom, fathering 20 children by two wives. His first wife, Ann Hart, bore him 11 children between 1792 and 1809. Seven of their children died as babies. Three of their daughters were given the name Mary Ann, but none survived more than a year or two. Not a good period to be named Mary Ann!

Ann died in 1815 aged 46. Less than a year later, William married Sarah Dawson at St Stephen's Walbrook, a short distance north of the Thames. The domed building was erected to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren following the destruction of its medieval predecessor in the Great Fire of London in 1666:

William was 47 and Sarah 23. William died in April 1841 aged 71 at his home, 78 High Street, Southwark, which no longer exists. Sarah was also a hat maker. She continued with this craft until she emigrated to South Australia with a son, the Revd Francis W. Cox who became a leading light in the Congregational Church in Adelaide after four years in charge of the Congregational Church at Market Weighton in Yorkshire. His fascinating life is summarised HERE. Sarah and Francis both died in Adelaide and were buried in the West Terrace Cemetery. Sarah died in December 1865 aged 73; Francis in March 1904 aged 87.

It is unclear what sort of hats my ancestors made. Were they for men or for women or for both? Here is a selection of hats worn in the 1800s:

My ancestors in Southwark all lived a short distance from the church of St Saviour and St Mary, later to become Southwark Cathedral where local baptisms and marriages were required to take place. It is said to have been a place of Christian worship in various forms for more than a 1000 years:

Some of the Coxes were Protestant dissenters and attended the Revd Rowland Hill’s Surrey Chapel on Blackfriars Road junction with Union Street, Southwark. It had an interesting history.

The Surrey Chapel was originally built as an Independent Methodist and Congregational church in 1783 by the Revd. Rowland Hill. He said that he chose an octagonal structure so the Devil couldn't hide in the corners. In 1876 the congregation removed to the newly erected Christ Church in Westminster Bridge Road, and the old octagonal chapel was finally closed as a place of worship in 1881. It fell into disuse but in 1910 it was bought by a former boxer Dick Burge who, together with his wife Bella, turned it into a boxing and later a wrestling venue, attended by the rich and not so rich of south London. The Prince of Wales was a patron. In 1940 the building was damaged during the Blitz and in 1941 was completely destroyed in an air raid. The site is now occupied by a modern office building named Palestra House, the Greek name for a venue where wrestling takes place.

William and his family attended the Surrey Chapel. In addition to his long and apparently successful involvement in the hat trade, he also played a prominent part in the welfare of those less well off. The Minutes of St Saviour's Church (now Southwark Cathedral), London, dated April 18, 1830, showed that William was appointed a Warden and Overseer of the Poor. This job entailed keeping an eye on the workhouses, lunatic asylums, apprentices, orphanages etc, and also to check on the paid parish officials.

On Thursday, March 29, 1837, he was appointed Chairman of the Board of Guardians, at a meeting held in the Christ Church workhouse in Southwark. An extract from the Minutes includes this report, which gives an indication of the sort of problems facing society: "The Visiting Committee in discharge of their duty visiting this House in Sunday last, examining the serving of dinner, which was anything but satisfactory to the inmates and exceedingly painful to the feelings of the Committee. The meat was very hard and of such inferior quality that your committee will hope it will not continue, chiefly consisting of stickings [neck meat] of the worst sort of beef, which at the best is only fit for soup. Mutton was not of that sort, so we could recommend to the sick poor; indeed the Committee stated some considerable blame to be attached to the Master for not insisting upon the words of the contract being complied with literally, in receiving into the House in other than equal proportions of good Ox Beef in thick flanks, Leg Mutton pieces, clodes [lumps] of stickings which they recommend the Board to insist upon having delivered into the House in equal proportions, in place of the present plan of the very coarsest clods [neck meat] and stickings, only. When the Board takes into account the instruction that only five ounces of meat, served out on Sunday, and that the inmates have had none from the preceding Thursday; it ought to be of such a quality as to afford some nourishment."

There were reports that William was "well acquainted" with John Wesley, but the Wesley Historical Society has been unable to turn up any reference to William and says it is doubtful that William Cox and John Wesley knew each other very well.

The last Will and Testament of William Cox of 78 High Street Borough Southwark:

“I leave and bequeath unto my beloved wife Sarah Cox the whole of my property and appoint her the whole and sold Executrix signed this 4th day of October 1840. William Cox. Signed in the presence of us and each other Oct 4 1840. [solicitors?] B.A. Tomkins 85 Bow Robert Kent(?) Thomas 46 Watling St City.”

Earlier chapters can be found HERE

As always lan a very interesting read.

The research you and Rosemary have done over the years is absolutely amazing..

Thanks again for the journey..l enjoyed it ...

Cheers to you both ...

Helen Australia 🇦🇺 🥰

Couldn't add anything else to Helen's comments Ike. Enjoy the history immensely.

Are Ruth and Allison still residents of Oz?

Peter Hudgson