Chapter 19: Autograph hunting and a start at the BBC

As with previous chapters, I have drawn on the information contained in my diaries and family letters for accuracy…

Rosemary, who began collecting autographs as a teenager, beginning with the autographs of sportsmen participating in the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, continued with this hobby over here. Among her prizes is the signature of UK prime minister Harold Wilson. As a bonus she was sent a Christmas Card signed by him.

Harold Wilson must be running short of friends, but it impressed our landlords to see us receive envelopes from 10 Downing Street. Rosemary also got the autograph of former UK prime minister, Sir Alec Douglas Home, but no Christmas card from him!

Rosemary’s best autograph prize remains that of the Soviet astronaut Yuri Gagarin, gained when we were still in Melbourne. There was a Russian girl working in a café close to where we lived in the suburb of Prahran and she translated Rosemary’s letter to Gagarin into Russian. About a month after it was posted to Russia, Gagarin died in a MiG-15 jet fighter crash. Rosemary assumed that her hopes of his autograph were dashed, but about a month after he died, a signed autograph and a signed card turned up in an envelope date-stamped just days before he was killed. It is reasonable to assume that these were possibly the last autographs he ever signed.

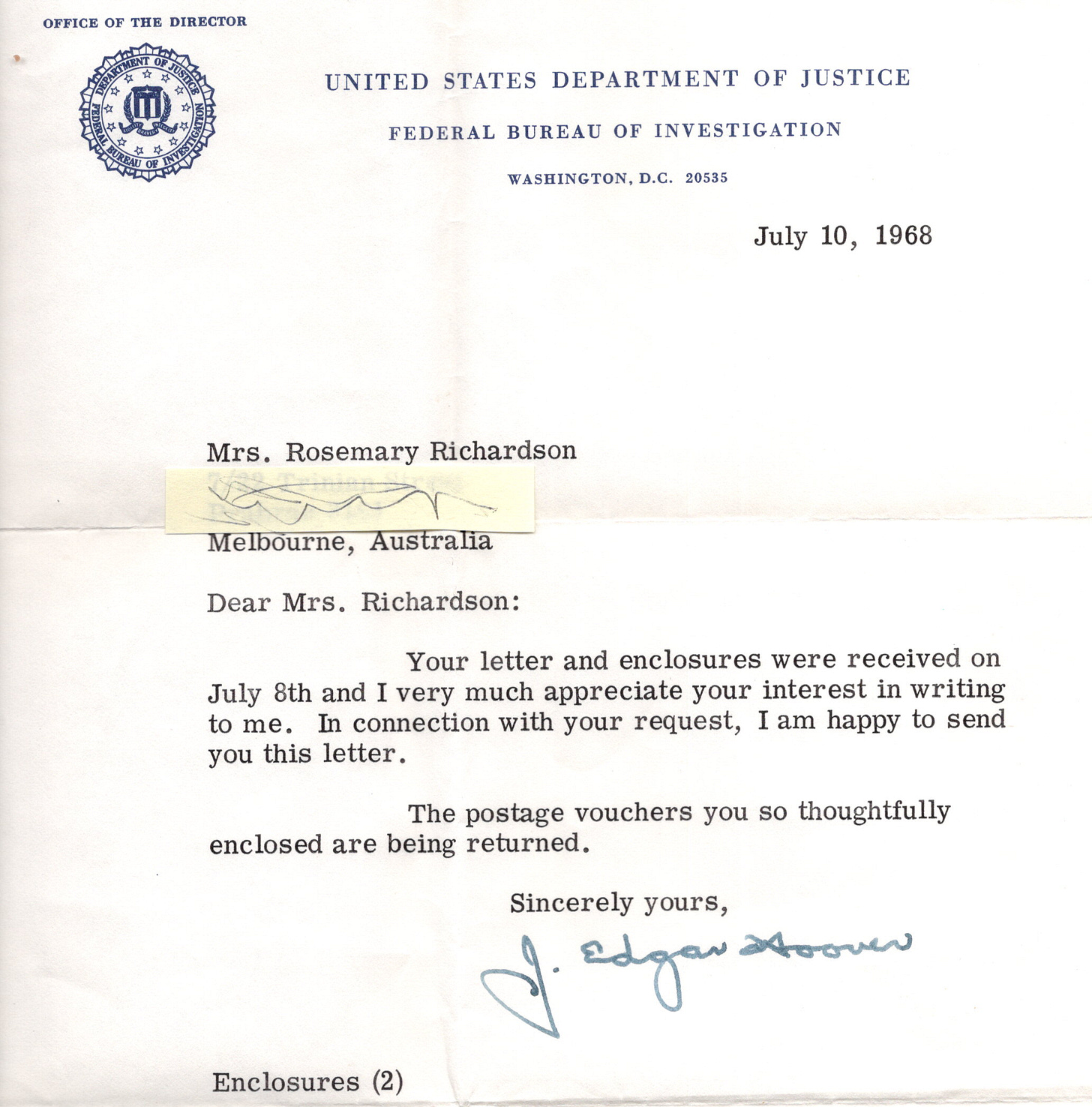

In all, before Rosemary stopped seeking autographs, she had more than 60 of the world’s most famous and distinguished persons. It’s a fascinating list, including Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor on the one card (Burton’s signature is small and very neat, while Taylor's is big, flamboyant and scrawly). Rosemary also has the autographs of Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, Golda Meir, Marlene Dietrich, Agatha Christie and a letter from the FBI boss, J. Edgar Hoover.

It’s possible that some of the signatures are actually those of a secretary or other staff member or by autopen, but even so, the majority are clearly genuine. One of her prizes was a card with the autographs of the Beatles, but it is suggested that not all four of them are genuine. Difficult to tell.

A further prize is a letter from the British comedian, Tony Hancock. We saw him perform at the Dendy Theatre in Melbourne, but he was drunk and a great disappointment. Even so, Rosemary wrote to him asking for his autograph and received this letter almost a year later:

Tony Hancock killed himself in Sydney on June 25, 1968.

****

A majority of firms in London issue staff with Luncheon Vouchers. These are worth three shillings each and are accepted as payment in most cafes. They are popular because they are tax free.

****

We are thinking of tracing our family tree. The idea began when Rosemary received a letter from an auntie giving a broad outline of the Batson family tree. We’ve been told it should “not be too hard for us to trace the various branches of our families”. God knows who, or what, we will turn up.

****

I was given a pay rise by the Institute of Marketing, where I was still working as secretary to the Company Secretary. I now get £19-10-0 a week with £5 taken out in tax. This is a lot more than many of the locals doing my sort of work get paid.

****

These are extract from letters to my family…

March 1969: The Home Office has written to confirm that Rosemary and I have unrestricted entry into Britain by virtue of my father being born in Scotland and Rosemary being married to me. I have also received word from the BBC that I have been short-listed for a job with the External Services Newsroom. I have been required to sit a two-and-a-half hour written test followed by a half hour grilling by an appointments board. Despite this, I have been warned that I might have to wait another two months for a decision. You would think they were looking for a new Director-General rather a lowly sub-editor.

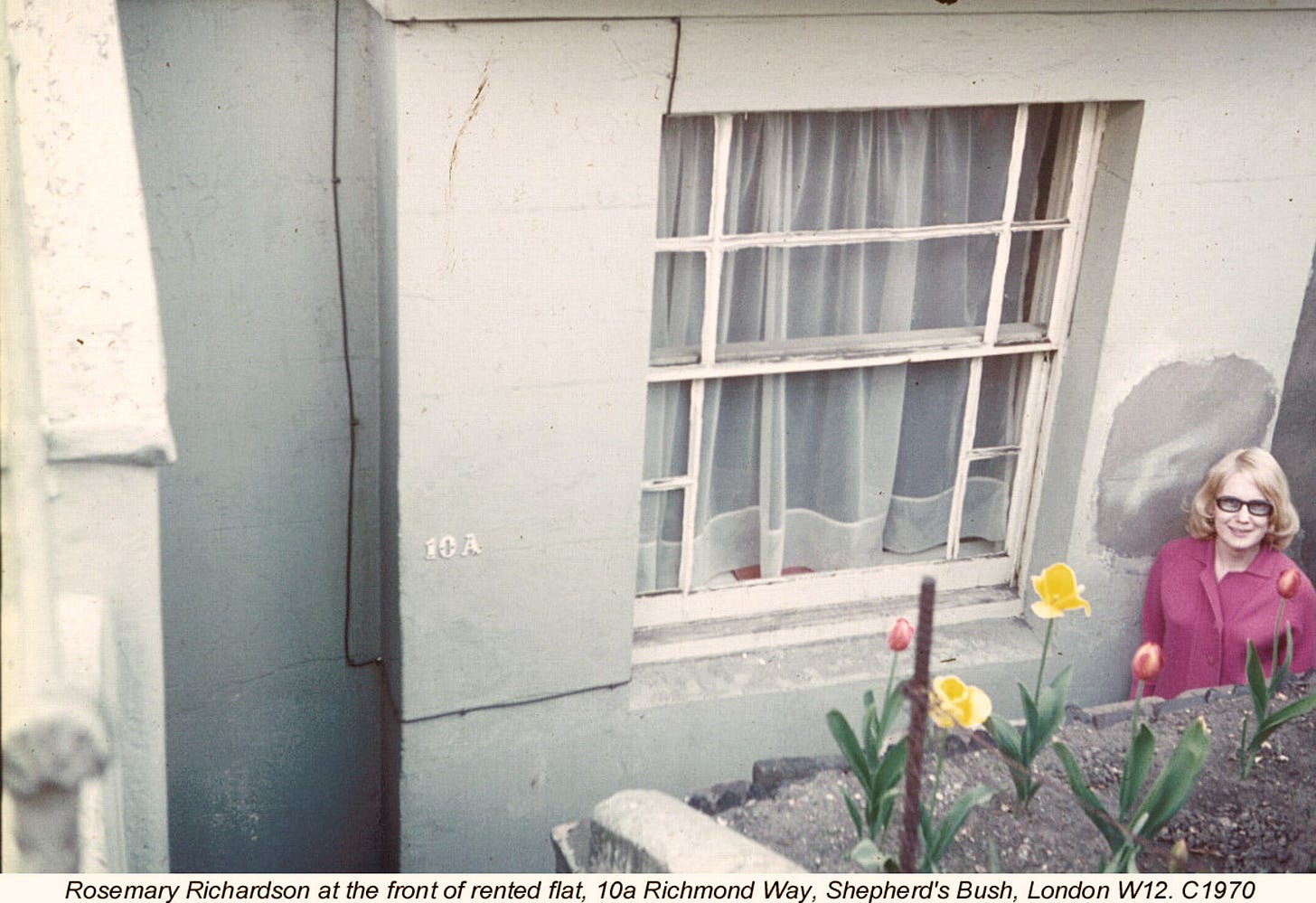

May 1969: We’ve moved to Shepherd’s Bush — a great improvement on our bed-sitter in Bounds Green. The address is 10a Richmond Way, W12, which is much closer to the city centre. It’s the ground floor of a three storey house. Its title, according to the lease, is The Garden Flat, which does seem a wee bit pretentious. There is another flat above it.

14 Warwick Road served us well, but it was restricting due to a lack of space. Rosemary was finding the walls pressing in on her and the long underground trip to work each day a drag. We are now only a stone’s throw from the Shepherd’s Bush underground station, with two other underground stations within half a mile. The new flat is fully furnished right down to such things as tea towels and dusters, and the rent is £8.10.0 a week, which is a real bargain in London.

I hadn’t realised just how uncivilised our living in England had been until we moved into the flat. What a joy to have the luxury of a refrigerator and our own bathroom. And there were no mice.

The flat could hardly be better situated. A huge shopping centre is being built immediately behind us. We are also in the midst of a shopping centre that stretches in almost every direction as far as our feet will carry us. Half-a-mile away is a big market that has on sale everything from hairpins to new gas stoves. It is very much like the Victoria Market in Melbourne. And across the road from the flat is a lovely pub. Most important! The back garden just needed tidying and I was permitted to build a basic barbecue.

May 11, 1969: At last, a job with the BBC. My contract as a sub-editor is initially for the period to September/October, but if I want to (and there are sufficient vacancies) I can apply for an extension. Naturally, I am very thrilled to have won the job against such stiff competition, even though the money — £38 per week — is quite a bit less than what I would be getting in Australia. The professional status of having worked for the BBC should pay enormous dividends in the future.

The Institute of Marketing was very kind to me when I left. Although I had been there only four months, I was given a beautiful pair of cufflinks. Most unexpected.

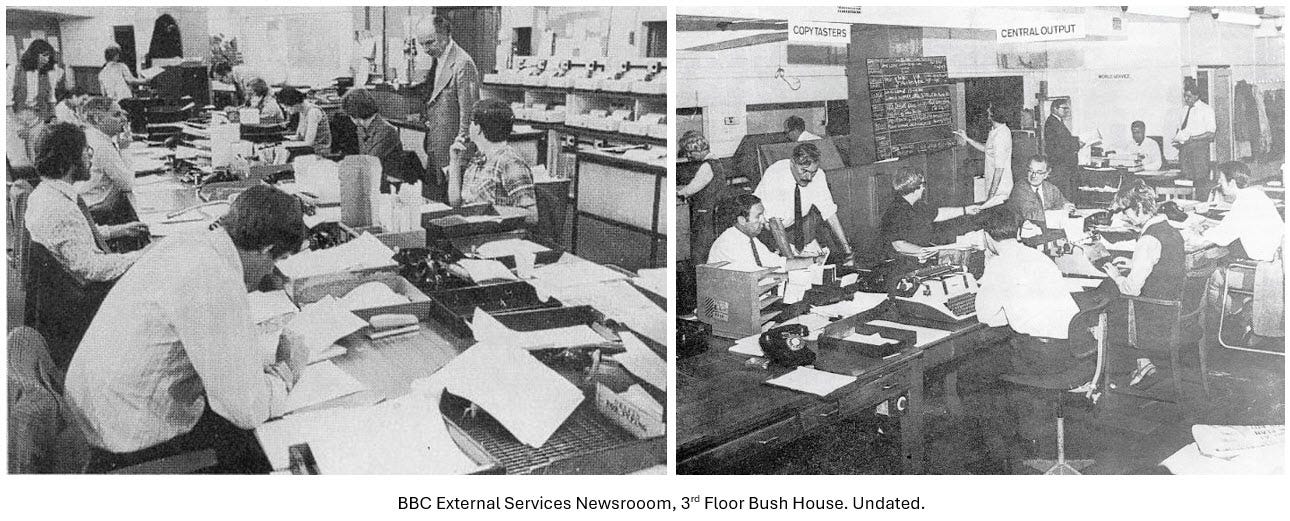

The BBC, once it gets around to pulling its finger out, doesn’t muck about. The letter saying I had been accepted for the job said, "we would be happy to have you start immediately". I phoned to enquire what was meant exactly by "immediately" and was hopefully asked “what about tomorrow?" This was too soon, but I was able to start a week later. My first shift lasted just five hours, and was strictly for “looking and listening”.

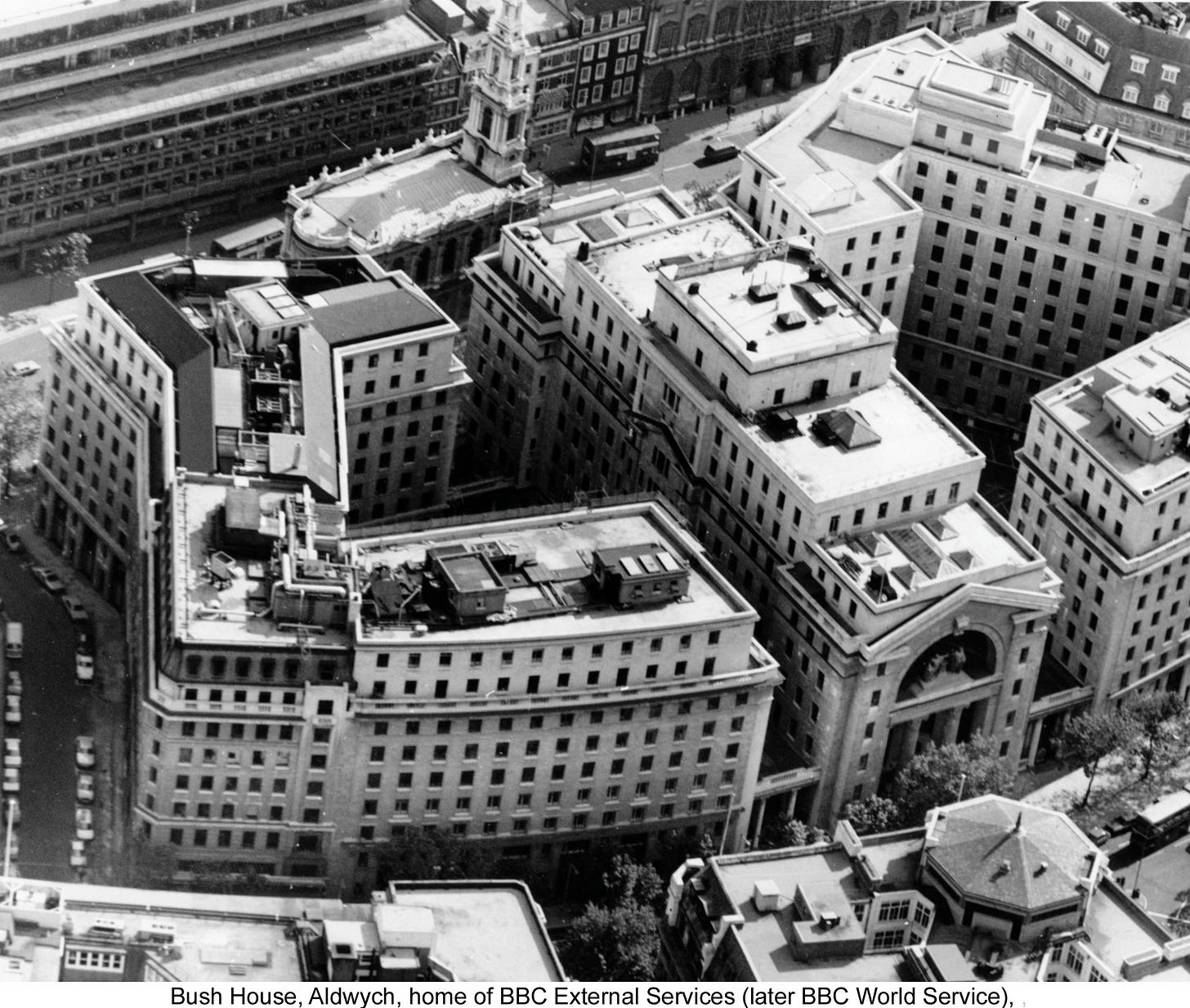

About a hundred sub-editors, chief sub-editors and editors work in the newsroom at Bush House, and I believe the BBC staff in the building totals about 3000. My normal roster will be three days 8.00am to 3.30pm, three days 3.30pm to 11.00pm and three days off. A very satisfactory arrangement. In due course, I will also be required to work occasional shifts from 11pm to 7am.

The newsroom is crawling with Australasians. On my first shift there were six Australians (three sub-editors and three typists) and at least two New Zealanders.

The pace is very, very much slower than at 3AW, and I can’t imagine anyone getting ulcers. Every story goes through an elaborate checking process to make it as accurate as is humanly possible. Only on very rare occasions does the BBC run information that has come from fewer than two sources. Every desk in the newsroom is supplied with a full set of the daily papers (about eight) and there is loads of time in a shift to get through the lot. Bush House, where the overseas service is housed, is immediately beside Australia House, just where The Strand becomes Fleet Street. From my desk, I look down on the Victorian Government offices.

May 17, 1969: I’m starting to settle in at the BBC, although it will take some time to adjust to the rather stilted writing style after the racy 3AW approach. I’ve had to attend two indoctrination courses with a panel of senior news people keen to explain the BBC ethos and what would be expected of newcomers, such as me. When I applied for the BBC job, I was told that I was up against about 50 others, but an assistant editor told me this week that the figure was actually 100. I don’t think I’d have had the audacity to apply if I’d known this.

My mother, Rena, will be interested to know that one of the women journalists in the newsroom is also Rena (Stewart). Female journalists are a minority in the Bush House newsroom, but they include Nancy Kelk, a Polish countess, Lady Susan Hare, plus a dreadful talent-free snob and a woman who makes no secrecy of her racism.

May 24, 1969: I am writing this letter at work in one of my many spare moments. The BBC’s policy seems to be to carry enough staff to handle any sort of crisis, including a nuclear war. Although the BBC has been modernised in many ways, there is still evidence of its quaint past. Take, for instance, the announcer with the handlebar moustache who reads the news with a monocle! And there are others who smoke while reading the news.

June 1, 1969: I began arrangements to interview Mick Jagger about this ridiculous business of him playing Ned Kelly in a film. An hour after I spoke to his office, the police raided him and found drugs. The tipping here is that he’ll be sent to jail because of his prior conviction. So, it will be bye-bye “Ned” Jagger and bye-bye interview. (The film did get made in 1970.)

Life at the BBC continues to jog along at a leisurely pace, but I am getting a little bit more work. I was heartened to hear from a veteran here that when he started, he did one shift in which he didn’t touch his typewriter.

June 8, 1969: Rosemary is back on the sewing, much to her delight. She bought an ancient Jones Family Company machine, which is operated by hand. It cost only £8 and is a little beauty, although she is having to get used to working the machine with one hand and holding the material with the other. According to the label it is “as made for Queen Alexandra”. The BBC library says this probably means the machine was made some time between 1870 and 1920.

Yesterday, I did my first day of really hard graft with the BBC. I arrived for work to find that one of the two copy tasters (the people who collate all the inward cables and decide what material will make a story) had not turned up. I got the job and found myself sitting at the centre desk with all the bosses. I was absolutely terrified because it is a very important job and one in which -- as one copy taster put it -- you never do the right thing in the eyes of the editors. Still, not once did anyone scream at me, so I can’t have done anything disastrous. Once I got over the initial shook of being thrown into the job, I decided that if the BBC was stupid enough to trust a rank newcomer, the rank newcomer was stupid enough to have a go.

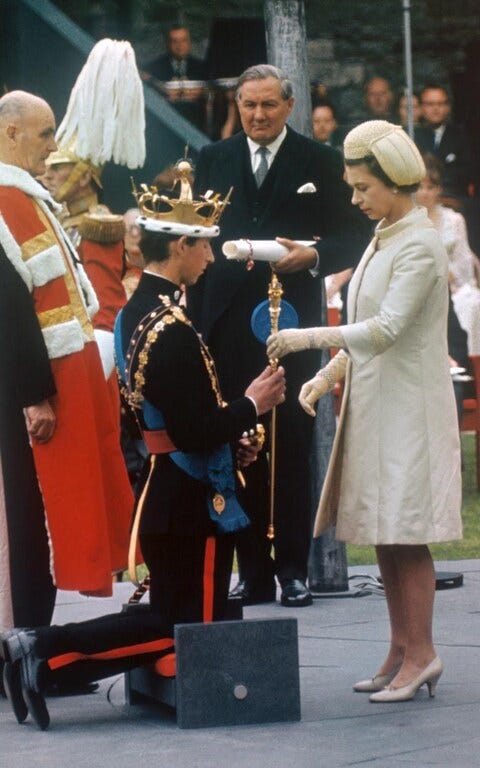

June 28, 1969: A break from the BBC. Our trip to Wales to cover the investiture of Prince Charles in Caenarfon Castle for 3AW Mebourne...

It has been decided that I will do a live chat with commentator Norman Banks, in addition to the pre-recorded report for the breakfast news. Both the report and the chat will be done by telephone. It’s going to be quite exciting to do the actual “international” coverage, although in all honesty the investiture is 99% nonsense. Because of the global television coverage, 3AW would be able to write as good (if not better) story than me by just sitting in front of the TV set in the newsroom in Melbourne but the station liked to claim “we have our own special correspondent on the very spot”.

After spending the night in our van on a camping site, we arose on investiture day feeling rather weary. About 9am we drove to Caernarfon along the processional route to the press parking area just across from the castle. We had not seen so many policemen in all our lives. They were literally shoulder-to-shoulder in most places. Even though our van was carrying an official Press sticker, police still questioned us about what we had in the back, and I had to keep producing my police press pass to move from one spot to another. The security was fantastic, with helicopters and jet fighters frequently flying overhead and cops and soldiers at every turn.

Very few newsmen were allowed into the castle, so we took up a most comfortable position on a grassy slope about a hundred yards from the castle and across from the last section of the processional route and the gate where everyone entered and left. With the aid of the binoculars bought by Mum in Hong Kong some years back, we had a marvellous view of all the comings and goings and of the presentation of Prince Charles to the people of Wales. What little we couldn’t hear from the castle itself, we listened to on our transistor radio. Although we were both dead tired, it was a thrill to have been there and to have seen at least some of the proceedings.

After phoning through my first report to 3AW, we set off for Betws-y-coed (roughly pronounced, betters-E-ko-ed) where we were booked in for the night at the Riverside Hotel. We arrived about 8pm, and although rapidly approaching total exhaustion, we were unable to go to bed because I had to make another phone call shortly before midnight to do a live interview with Norman Banks and to record another news piece for the midday news. We had been eagerly looking forward to a bath, having not had the facilities or the time for a decent wash since setting out from London. But when we asked about a bath we were told: “Sorry dears, but we’ve lost the key to the bathroom and we can’t get into it”. So, no bath. Still, we were so tired I think we could have slept even if we had to share the bed with bed bugs.

We arose next morning feeling considerably better and ravenously ate our breakfast. We were surprised on checking out that the bill for the two of us – dinner, bed and breakfast – was only £4. And the woman owner apologised for having recently increased the charge! Charles was due to pass through Betws-y-coed that morning, so after loading up the van, we strolled down to the other end of the village and joined the “fans”. The Royal car slowed down as it passed us, and we got quite a good view.

July 12, 1969: Back in London. I'm getting more interesting and responsible work at the BBC these days. I’ve been doing quite a bit of work preparing bulletins for the African, Arabic and Asian services, and this makes the day go quicker. I’ve also done one Dawn Shift (11pm to 7am), which was fairly busy for four hours, then deathly still in the remaining four. I did only 10 minutes work in the second half of the shift.

On Thursday night we lashed out and went out for dinner with Joan, Reg and Cheryl Gray/Sang. We went to the marvellous Samuel Pepys pub hidden away among all the tatty old warehouses on the Thames waterfront. We all thoroughly enjoyed tucking into beautiful juicy steaks. The cost for the three-course meal with drinks and tips came to 30 shillings each, which is pretty fantastic. This weekend, Cheryl is staying with us. She’s absolutely bored to tears waiting for her big launching as an international artist. She and Rosemary get on very well together, so she’s good company for Rosemary when I’m working weekends.

August 2, 1969: The government has just refused to allow TV or radio stations to extend their hours. In this city of about 10 million people there is no television before about 1pm and none after midnight. And only one of the four radio networks operates after midnight (and it closes at 2am). Breakfast sessions on radio don’t begin until about 7am.

August 10, 1969: There’s been some good news on my BBC work front. I have been told by the personnel officer that I will be offered a permanent contract when my temporary one runs out in September. So that’s one worry off my mind. It’s nice to know that I will continue to be among the country’s employed.

August 23, 1969: The big news is that Cheryl (or Samantha) and her parents are being thrown out of Britain at the end of August because her work visa has expired. We arrived at their place last night to find it full of reporters and photographers getting the story. So the Grays are off to America at the end of the month while Cheryl’s manager, Robert Stigwood, tries to sort things out. To make things really tough, her new record was released only yesterday. Stigwood is spending a fortune on her. Every pop music magazine in Britain this week carries a full-page ad about her. The Grays are going to have to put most of their belongings in storage at our flat, because they’re only able to take a case each with them.

We have finally hired a decent TV set with a proper outdoor aerial. Oh what a joy to see a picture in focus again. I’d have loved to get a colour set, but they are too expensive. The hire cost (most people hire here) is a minimum of 25/- a week, compared with 10/- for black-and-white.

September 7, 1969: The Grays/Sangs are now in New York for the launching of Cheryl's record Love of a Woman. It got very good play over here, and we heard it today on the joint BBC-ABC World Wide Family Favourites request program. Why did Cheryl change her name to Samantha Sang? Well, her real surname is Sang (her ancestors were a feudalistic Chinese family forced to flee to Australia early last century) and her manager didn’t like Cheryl because it was “too pretty” for a sophisticated nightclub performer. Hence the rather lush Samantha Sang. The Grays/Sangs didn’t like it at first. Nor did we — but it grew on us.

Next chapter: Life continues at the UK and the BBC, plus travels around Europe.

As always Ian ..another interesting read ..so happy how much Rosemary has been mentioned ..you're a great team together...cheers to you both and waiting for the next chapter ...Helen 🇦🇺