Chapter 10: Charlton - my final years as resident

I’m told that I should confess to having a criminal past in my sub-teens. I collected a lot of ha’pennies with the intention of doubling their value by laying them on the railway lines before an approaching steam locomotive flattened them into the size of a penny. I tried to buy sweets with the “pennies” but they were rapidly rejected by shop keepers. So I lost both my ha’pennies and my “pennies” and I came to the conclusion that a life of crime was not for me.

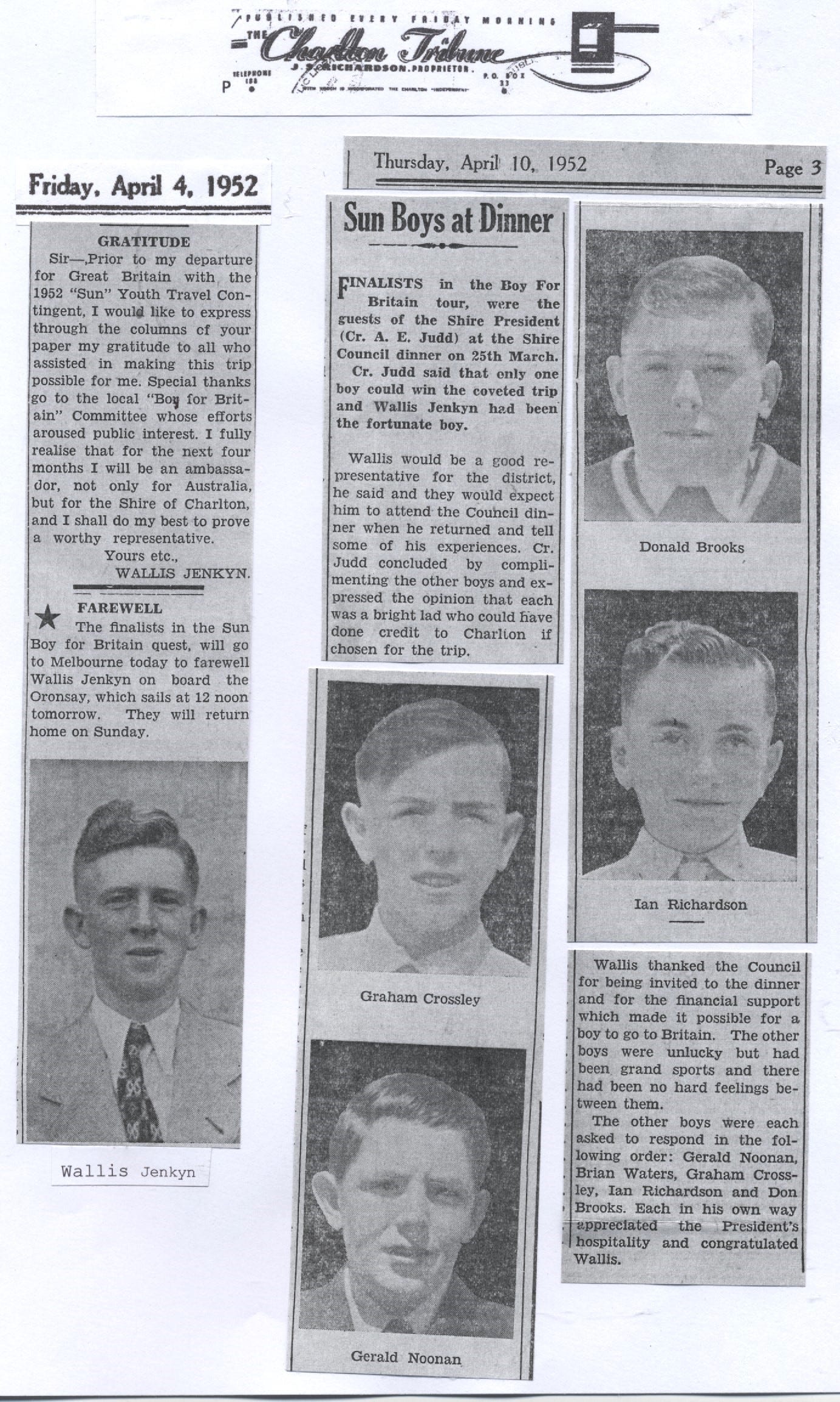

The Sun newspaper ran an annual Boy for Britain in most towns. I came second twice — once to Bob Allison, son of the then Higher Elementary School headmaster, then to Wallis Jenkin. I guess I would have been disappointed not to get an each-way ship voyage to London and six weeks touring the UK, but I was not to know that I would end up living in London anyway.

During my stint as scout leader we were taken to the Rheola Caves about 30kms from Charlton. I don’t know how we got there, but it was quite an adventure, with a strong element of stupidity on my part. As we explored the caves, I found what looked like an interesting tunnel so decided to explore it on my hands and knees, followed by the other scouts. The tunnel turned out to be longer and narrower than expected and there came a point where I wondered whether we should turn back. But how? This would have been incredibly difficult. So we pressed on and finally saw light and found ourselves, much relieved, on the other side of a hill and able to find our way back, by foot, to the opening of the caves. I don’t think we told our parents what we had done.

For a year or so, Mum’s sister Marjory lived with us and worked as a secretary for Noske’s Flour Mill. Her father, A J G Cox, sent her to Charlton in the hope that this would kill off her engagement to George Kilgour who lived in Melbourne. It didn’t. They wrote to each just about every day and George would also make frequent visits to Charlton. He won over my heart by making me a beautiful cane fishing rod. I was also hugely impressed by his ownership of a Singer sports car that would do 60mph around a corner.

George and Marjory eventually married but they had very contrasting — I would say extreme — religious views and the marriage was a disaster.

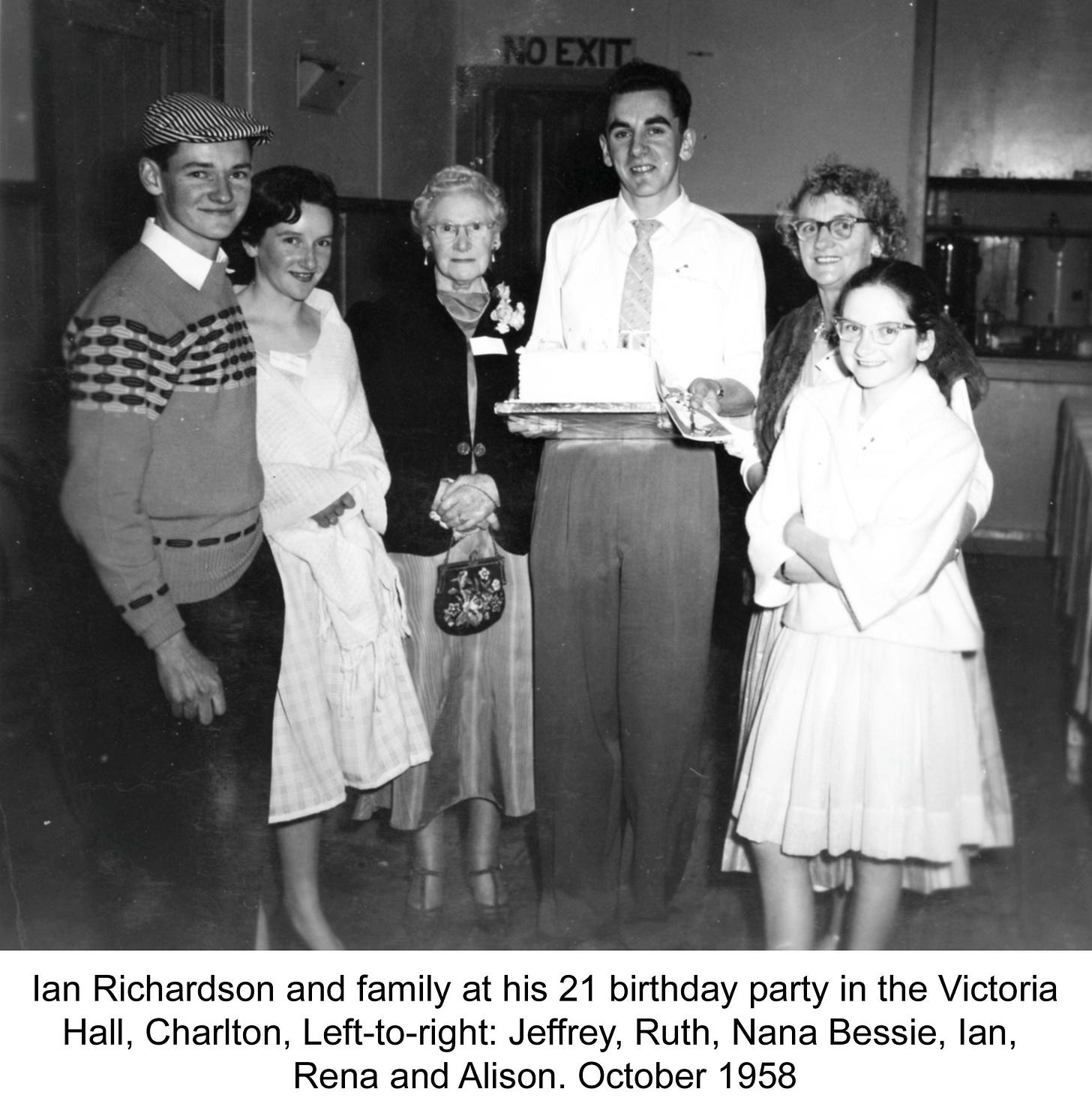

My 21st birthday was held at the Victoria Hall in Charlton and was quite an event with a large turn-out from Charlton and Quambatook. Here’s a group photo:

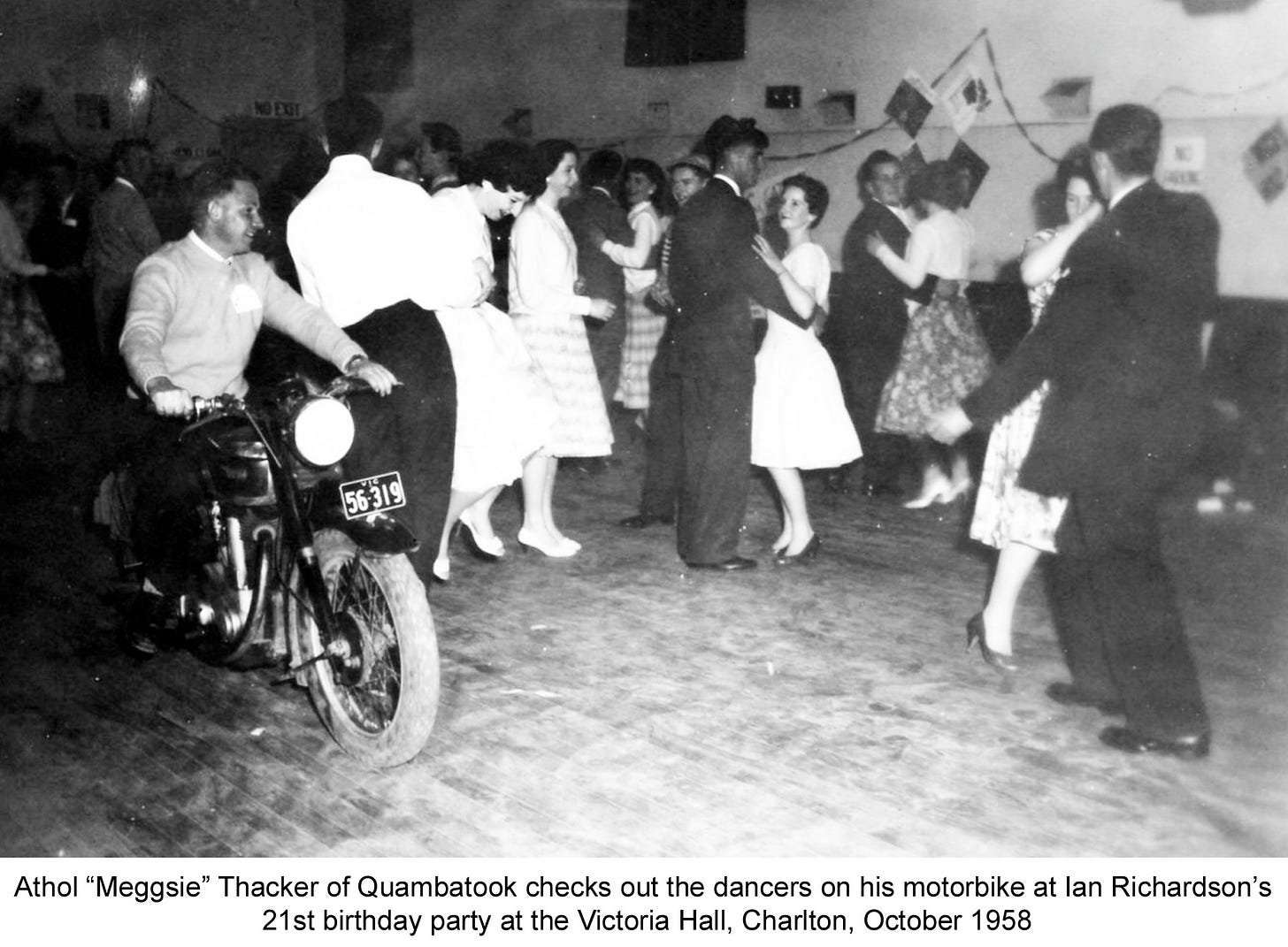

And here is a photo that made the event look wilder than it really was. For starters, there was no alcohol at the party. I didn’t have my first alcoholic drink until much later. My late father was teetotal and wouldn’t even allow sherry to be put in Christmas cake, even though all the alcohol would have evaporated in the cooking.

As you will see, I was significantly taller than the rest of my family. This led me to wonder if I had been adopted. I wasn’t. It was just that I descended from my taller maternal Cox/Sutton line rather than the Scottish Richardson line. This was confirmed much later by a DNA test.

The next part of my story is arguable one of the most difficult to write. It is about my mother Rena’s marriage to a wealthy Charlton district farmer, William Herbert “Bill” Wood. Bill was a distinguished member of the community, being among many things a leading shire councillor, a leading Rotarian, a leading Freemason, a talented sportsman and a private financier. But there were two contrasting Bill Woods and my mother married both of them.

Let’s begin with this timeline:

February 11, 1958: Bill was widowed when his wife Audrey died aged 57.

Unknown date: Bill began a relationship with Marjorie McDonald, manager of Judd’s mixed goods store in Charlton.

August 2, 1959: There was no formal announcement of an engagement, but there was a pre-wedding sing-song and gift presentation to Marjorie after the evening service at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church with a reference to her being married to Bill “shortly”.

September 5, 1959: Marjorie died in Melbourne from an undeclared illness.

October 1959: Bill began a secret relationship with my mother. This eventually became public.

February 19, 1960: There was no formal engagement announcement and Bill and my mother were married at the Wesley Methodist Church, Melbourne.

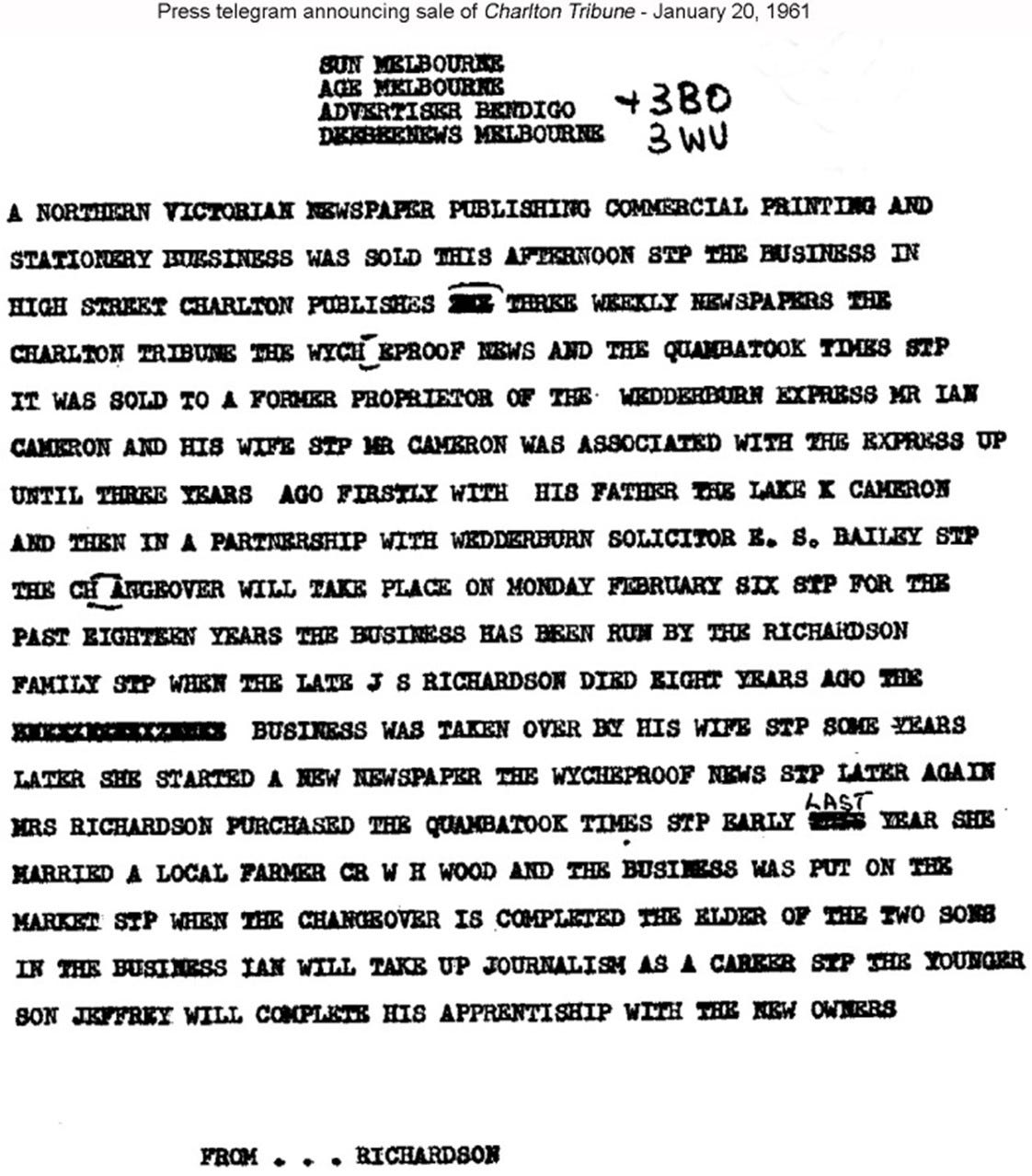

In January 1961: My mother sold her newspaper and commercial printing business to Ian and Coral Cameron.

There is no doubt that the town owed Bill a great deal for his community activities, but there was another, unpleasant, side to his character that few people realised.

For myself and my siblings the rot set in immediately after their honeymoon. In the run up to the marriage, Bill had oozed charm, so much so that we put to one side the alarm bells that rang about the speed in which he moved on from Marjorie McDonald to our mother. We were given an assurance that while Mum would move in with Bill at 14 Mildura Way we children would remain at 10 Peel Street. But that lasted no time. We were soon ordered to move to Mildura Way and the Peel Street property was sold. Youngest sibling Alison was soon sent off as a boarder at the Clarendon Presbyterian Ladies College in Ballarat. Bill’s attitude to Jeffrey, Ruth and me changed dramatically and we soon saw the other Bill Wood. We were also to learn that his relationship with his two sons, Jack and Ted, was almost as bad, if not worse.

I may not have been a perfect step son, but it is no exaggeration to describe his attitude to me as one of contempt.

The first few years of the marriage went well. After so many years of austerity, Mum loved being with a husband who had so much money to splash around. It was almost as though Bill had his own banknote printing press. For him, it was wonderful to have a good-looking outgoing woman accompanying him on his travels for Rotary around Australia and abroad. She was not just his social secretary but also drafted many of his speeches. Then at some point — it may have been after his stroke — the relationship turned seriously sour and stayed that way until Bill died in May 1985. Mum frequently threatened to leave Bill, but we knew she never would. It was almost as if she and Bill stayed together to torment each other.

Because of his extensive community activities, Bill had many admirers and acquaintances, but few real friends. I can remember just one: Ike Richards, the town jeweller. Ike had a standing invitation to an evening meal — usually a roast — every Thursday. Their conversation was strangely identical for each visit as though they were both reading from a script.

A real low point in the marriage came after my mother visited us in London. On her return to Australia, she was delayed in Singapore for a couple of days. Bill got it into his head that Mum was having an affair with Rosemary’s 90-year-old New Zealand relative who had been visiting the UK about the same time. This was utter nonsense. When Mum arrived back at Tullamarine Airport in Melbourne, Bill had to be restrained from assaulting her with his walking stick. Bad enough. But we were later to learn that while Mum was in London, Bill was trying it on — unsuccessfully — with two of her sisters.

When Bill died he left a will that was intended to cause the maximum grief within the family. His sons, Jack and Ted, were to receive nothing, while Mum was allowed to continue to live in the marital home in Rosebud on $3,000 per year. The ultimate beneficiaries were to be Bill’s six grand children. His solicitor told him that the will would not stand up to a legal challenge, but he refused to back down. Inevitably, the legal battle that followed his death resulted in huge rows between the two brothers and between them and my family. Eventually there was a reasonable settlement for Mum, but probably not for Jack and Ted. Although Ted and his wife Margaret became good friends to our family, Jack died a bitter man, refusing to have any contact with us or with Ted.

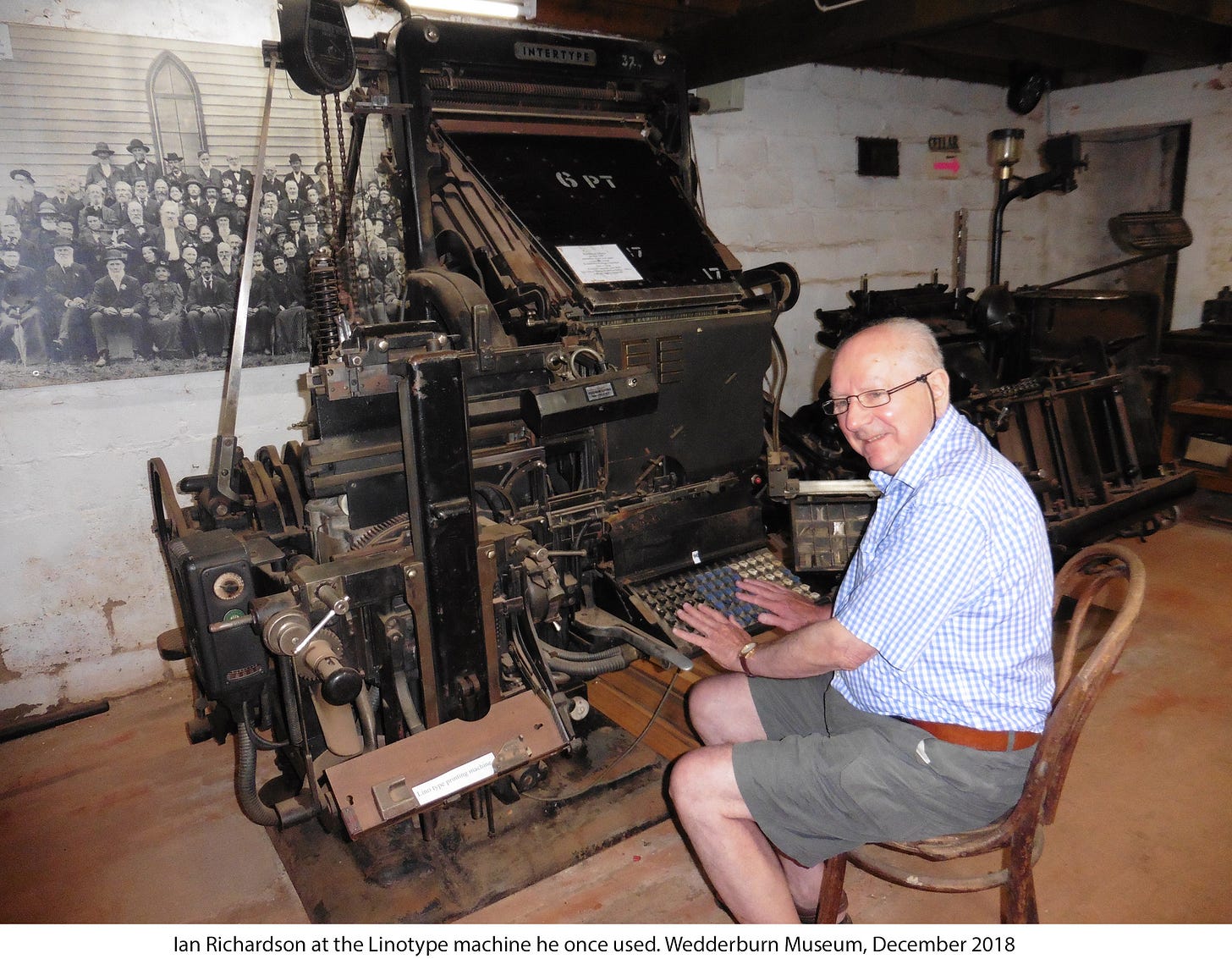

After my mother sold the Tribune business to the Camerons in 1961, Jeffrey and I were kept on for a while. At the same time, the Express newspaper in the neighbouring gold mining town of Wedderburn had been bought by Eric Shackleton Bailey in partnership with the printer, John Somerville. The Wedderburn Express was completely handset, which was a very laborious task, so “Shack” invested in a Linotype. As John didn’t know how to operate it, Ian Cameron, whose father had owned the Express for many years, loaned me to “Shack” and John one day a week to teach John how to operate and maintain it. I guess I did that for a few weeks until I was no longer needed. (After the Express closed some years later, “Shack” moved to Coogee in New South Wales, then back to England where he married Carmelina Mackay in Blackpool shortly before he died.)

On a visit to Australia in December 2018, I was tipped off that the exact Linotype now resided in the wonderful Wedderburn Museum which I was able to visit before returning to London:

Ever since I had returned to Charlton from Shepparton I had acted as stringer (correspondent) for a number of outlets including the ABC, Radio 3BO Bendigo, and Radio 3DB Melbourne and DB’s regional station 3LK at Lubeck in the Wimmera. It was this that led to my being invited to move into radio news by the editor of 3BO News, David Horsfall.

Next chapter: My time with 3BO and how I met my wife, Rosemary Batson, on the dance floor.

A difficult subject well written, Ian.